The expedition leaders Capts Wingfield & Gosnold recruited 40% of the settlers and were founders of “The Cradle of the Nation.”

This below an imaginary monologue (with both audio and visual text)– with more than two-thirds in Wingfield’s original words – “voiced” in England in 1620 by Captain Edward-Maria Wingfield at Fotheringhay College House, his stepfather’s home, when the old President was aged 70, at “Part 2. Jamestown and after’ ” to “On my return from Virginia.”

Every fact can be proved from primary sources – including many “new” or ignored sources unearthed over 50 years and used in 1993 by me, Major Jocelyn R. Wingfield of Norfolk, England, his biographer.

In a very few instances – where a fact is merely extremely probable but cannot be proven, the expressions “as I recall” or “I believe” have been used. (Added – perhaps unrealistically – are the first names of the settlers – so that we may honor them all in this great team effort of founding “the soul of the nation”: the first English-speaking colony in what is today’s USA).

It was the old veteran soldier Captain Edward-Maria Wingfield, who in 1606 when aged 56, financially rescued his and Bartholomew Gosnold’s planned expedition, and who aged 57 was President at Jamestown in Virginia in the first four vital months there from May 12th to September 10th, 1607, when he built the great fort in a month and a day, started planting and initiated bartering with the native Americans.

Here in his old age, aged 70 in 1620 – he was still living in the year of the “Mayflower” – the old President reminisces. (Passages are in his own words, taken from his “A Discourse of Virginia”, written immediately on his return, probably at Stonely Priory. In this monologue where he has written “the President” or “he”, I have sometimes changed it to the first person; and I have modernized the spelling and punctuation and sometimes the word order, adding synonyms of ancient words and adding omitted words – or the odd additional word to help modernize an expression.

Compiled and edited by Jocelyn R. Wingfield, President Wingfield’s biographer

Except for the Stonely Deed, MS22A/4, any part of this monologue may be copied provided that (1) The text remains unchanged and in complete sentences, (2) That the title “President Wingfield Speaks (1620)” and the page & note number quoted, and (3) That the following courtesy line is given: “Courtesy of the Wingfield Family Society”.

I was born in 1501 and was brung up at Stonely Priory (near Huntingdon, some 100 miles north of London), until I was seven, when my father, Thomas-Maria Wingfield, died.

The added name of “Maria” came from my father having had Queen Mary of France (sister of England’s King Henry the Eighth) as his godmother. My father had held at least 5,600 acres – most of it in trust for my cousin, Thomas Wingfield of Kimbolton Castle.

When my father died my siblings were: Thomas-Maria, Jr. (6), Gamaliel (4), Richard (about 2) and six sisters. Not too long afterwards my mother, Margaret, daughter of Edward Kay(e) of Woodsom, Yorkshire, remarried. So by the time I was 12 my new stepfather James Crews a.k.a. Cruwys2 of Fotheringhay College House had become my guardian.

Our new home – the former College of St. Mary and All Saints for three dozen chantry priests and choristers, from 1412 established to pray for the souls of Richard II, Henry IV and Henry V – lay 17 miles north of Stonely and in the next village to Apethorpe Hall, home of Anthony Mildmay, son of my Kimbolton cousin’s late guardian Sir Walter Mildmay.

My maternal grandfather, Rowland Sloper, was a London merchant, but my “patron” was my Uncle Jaques Wingfield, who was Master of the Ordnance in Ireland, and who held a manor called Wickham Skeith3 in Suffolk. This was the next manor to Wetheringsett – where in the early part of this century, the Reverend Richard Hakluyt, the great would-be colonizer of Virginia, was to be the priest.

I spent some years in my uncle’s “colony” in Munster in southern Ireland and then went to Furnivall’s Inn for a couple of years, prior to being accepted, aged 26 – which was not unusual – at the school for barristers (attorneys) at Lincoln’s Inn4 by London’s western city wall.

I did not complete the course, as after about three years there I volunteered to fight for the free Dutch in the Low Countries against their Spanish oppressors. My brother Thomas-Maria and I were each given a company of English foot to command.5 After a few years I returned to Ireland and in 1586 petitioned the Crown for some land in the west, but was not awarded any.

At Easter 1586, Thomas Norris, President of Munster, captured a would-be assassin of our gracious Queen, Elizabeth. And my cousin Sir George Carew and I had the task of escorting this infamous creature, Anthony De La Motte, this French-paid professional assassin, who was using the cover name of Baron Anthony de la Fage, to court for interrogation by the Queen’s spymaster, Sir Francis Walsingham, and Her Grace herself.6 To show her contempt for him, Her Grace was moved to release him – whereupon he made straight for his second target, which was the commander-in-chief of the allied forces in the Low Countries, the Earl of Leicester.

Sir George Carew forthwith, therefore, dispatched me to advise my uncle Philip Harvey at the Earl’s headquarters about the assassin roaming free on the continent, but unfortunately De La Motte arrived there before me – luckily to be apprehended. On my arrival I merely confirmed his identity.

In September 1586, together with my brother, Thomas-Maria, and cousins John Wingfield of Eresby (Lincolnshire), I fought the Spanish at the Battle of Zutphen (which battle the Dutch call Warnsfeld), on that foggy morning when John was knighted for his bravery.7 The wife of my brother Captain Thomas-Maria Wingfield, Etranildo – or was it Arlinda? (both his wives were Dutch) – lived not far from Zutphen.8

I believe that it was after I fought at the Battle of Zutphen that there was hard fighting at Sluys in 1587, in spring or summer 1588, the year of the great Spanish Armada, Geertruidenberg and Bergen-op-Zoom received maximum Spanish attention; and near Bergen, I believe it was, together with my comrades, Ferdinando Gorges (so keen on Virginian enterprises) and Conyers Clifford, I was captured by the Spanish.9 We were taken south some sixty miles to Lille and held to ransom – which demand arrived in England in September. In trying to raise my ransom, my brother captured two Spanish grandees: Don Inigo de Guevara, the future marquess and Don Luis de Godoya – literally worth a fortune10 – but the English commander removed my brother’s prisoners from him (although he did receive £957 a year later). However Sir Ferdinando, Clifford and I were included in an exchange of prisoners early in the following year (1589).

By sometime in that year my brother and I had seen some four years’ service, campaigning in the polders and dykes and moated, walled towns of the Low Countries. Indeed, I am proud to say that the Army Roll for that year was annotated – I presume by the great Lord Burghley – opposite the names of Sir William Drury, my brother and myself (only): “Captains of Success”.11

From about 1595 I was stationed in Ireland with my band of 60 foot-soldiers in garrison at Drogheda,12 the beautiful moated, walled town, 30 miles north of Dublin. I remember its great twin-battlemented St. Laurence’s Gate well. Our Muster Master was my old friend and neighbour from near Stonely, Sir Ralph Lane,13 who had been in the Roanoke Colony a decade earlier. Here I learned the art of skirmishing and how to deal with ambuscades from fighters hiding in bogs and deep woods. I remember two of my contemporaries were lost in ambuscades.

It was about this time that my old friend Sir Conyers Clifford and three of my Wingfield cousins sailed off on the famous Cadiz Raid. Indeed in Sir Richard Wingfield’s Regiment there was a young, difficult man called John Smith,14 who had begged a commission from him, and whom I was to meet later. He was a neighbour of my cousin, Sir John Wingfield of Withcoll & Eresby in Lincolnshire. And as son of a well-to-do farmer, John Smith had been raised with the children of the grand Willoughby family. Smith was to inherit property in Louth in Lincolnshire15 and at the turn of the century to be given equestrian lessons at Tattershall Castle by the Riding Master of his friend, the rather strange Earl of Clinton.

In 1599 I returned to Stonely in England and in 1600 I was made one of the feoffees or governors of Kimbolton School, a task I performed for about a dozen years.16 And here at Kimbolton I got to know Sir John Popham, who was most interested in settling Virginia. As Lord Chief Justice he had banished my cousin, the big-spending Sir Edward, “Ned” Wingfield of Kimbolton Castle – so keen on military expeditions and on jousting – to Ireland for his part in the Essex rebellion, and then proceeded to use Ned Wingfield’s home as his own. Meanwhile my next brother stayed on in Ireland, where he was made a colonel and knighted, and actually commanded the army in a tactical withdrawal from Yellow Ford.17

I sometimes visited the Wingfield ancestral home at Letheringham Old Hall in Suffolk. This lay 4 miles from the ancestral home of the Gosnold’s. And thus I got to know Bartholomew Gosnold, my cousin by marriage – who in 1602 had sailed to discover Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard. He was passionate about sailing to Virginia again and so many long hours – as I recall – we spent at his uncle’s house, Otley Hall, discussing this: routes, settler recruitment, leadership, financial backing and budgets, and not least, legality and stores. Sometimes present in the house was Bartholomew Gosnold’s younger brother, Captain Wingfield Gosnold18 – who was named for their step-grandmother, Catherine Wingfield nee Blennerhasset. And Bartholomew’s Aunt Ursula, wife of the distinguished-looking Justice Robert Gosnold the Younger of Otley Hall, was great-granddaughter of my cousin Elizabeth Wingfield. So we kept it all in the Wingfield-Gosnold family, as it were.

What I brought to these discussions – that was of great use – was what I had learned from my friends and comrades-in-arms about such ventures: from first, Sir Ferdinando Gorges, who had served with me in the Low Countries and had been held captive with me by those hated Spaniards in Lille in 1588; secondly, from Sir Ralph Lane, my old neighbour from near Stonely and my administrative chief as Muster Master in the 1590s in Ireland – whom, as I recall, I often met together with my cousin and his fellow general officer, Sir Richard Wingfield19 – as he then was – the Marshal of the Army there.

Sir Ralph, of course, had been Governor at Roanoke in 1585; and thirdly from the Lord Chief Justice, Sir John Popham (and his old brother George, who had sailed to Guiana with Sir Walter Raleigh in 1595, and who was to command at Sagadahoc when ten years older than me – that is aged about 67).20 I knew Sir John as a neighbour, since from 1600 he used to stay at Kimbolton Castle. He was often there, especially when masterminding his fen drainage operations. My old friend, Sir Ferdinando, now Governor of Plymouth, had been given – by Captain George Weymouth – three of the five native Americans (“Abenakis”) he had captured and Sir John Popham received the other two of these fascinating and sturdy-looking red men.21 I knew too the cleric and chief promoter of Virginia colonization, Richard Hakluyt the Younger, the great geographer – since he had been awarded the living of Wetheringsett-cum-Brockford with its lovely, great church – which lay just down the road from my family’s second ancestral home, Crowfield Hall, which belonged to my cousin, Harbottle Wingfield.

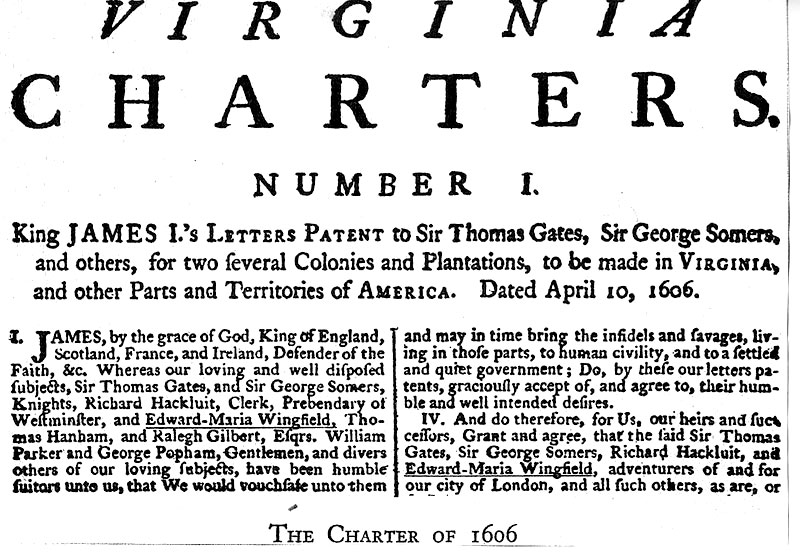

When our great Queen breathed her last in 1603, our new sovereign, King James VI of Scotland, arranged a peace with Spain and incarcerated Sir Walter Raleigh – which meant that Sir Walter’s Virginia patent became null and void. So, with great charge and industry the great geographer Mr. Hakluyt and we military men and merchants managed to petition His Majesty to approve the Virginia Charter of April 10th, 1605.

And I was proud to be named in fourth position in the “Big Eight”, together with Richard Hakluyt, George Popham, and Gates, Gilbert, Somers, Parker and Hanham.22 I believe His Majesty and Mr. Hakluyt and others wanted a Protestant leader for the London Company, who would not “affect a kingdom” – a “breakaway” colony, someone who was an old, wise and experienced military man – someone who had been a captain of success – but not a colonel, someone experienced in defense, skirmishing and in fighting the Spaniards. I was qualified – indeed perfectly so – and I was interested. I was only 56. The leader they selected for the northern colony – Sagadahoc – my old friend George Popham, was about 67.

So cousin Bartholomew and I set to recruiting settlers for our expedition. In London I had always stayed opposite St. Sepulchre’s, at the house of my cousin, Sir James Wingfield of Kimbolton, at St. Andrew’s, Holborn, where the parish rector had been Richard Bancroft, now the Archbishop of Canterbury. For my first work (which was to make a right choice of a spiritual pastor) … my Lord of Canterbury – His Grace…gave me very gracious audience in my request. And the world knoweth whom I took with me,23 truly, in my opinion, a man not in any way to be touched by the rebellious natures of a popish spirit, nor blemished with the least suspicion of a factious schismatic, whereof I had a special care: Robert Hunt. He was, I believe, a cousin of William Hunt, who was to marry Rebecca Wingfield, one of the seven daughters of my cousin and neighbour, Sir James Wingfield of Kimbolton.24

Next Bartholomew recruited his cousin and his nephew – both called Anthony and his old shipmates from the 1602 expedition: Mr. Gabriel Archer of nearby Manningtree (Essex) and Mr. John Martin (with his kin, John & George). We then persuaded some of those on and near the Wingfield and Gosnold estates of Letheringham and Otley to join us, including Mr. John Ratcliffe alias Sicklemore of Tuddenham (Suffolk), Mr. Thomas Jacob, and Mr. William Brewster and George Golding from Framlingham and nearby Cransford (Suffolk), and old Mr. Eustace Clovill from West Hanningfield (Essex) – who was I believe something to do with the Clovills of Westleton25 near Letheringham. I was also successful in persuading my cousin by marriage, Mr. Stephen Calthorpe,26 together with Mr. Thomas Studley, both of Norwich (Norfolk), to join me in Virginia; and Mr. Robert Beheathland, friend and kin of the Wingfields of Crowfield and of the Dades and Cornwallises of Tannington and Shotley (both in Suffolk).27

Then there were the settlers that I found near my home, Stonely Priory (Hunts): Mr. Jeremy Alicock from Sibbertoft,28 John Ashby, Mr. John Stevenson from Great Stukeley and I think Mr. Kenelm Throgmorton from Ellington,29 as well as tailor William Love and Mr. Edward Morris of Bluntisham (Hunts), Mr. Robert Fenton and bricklayer John Herd from Stamford (Lincs) – I think from a manor of my cousin, Sir John Wingfield of nearby Tickencote Hall. And then I found my cousin, Mr. Edward Harington from Exton (also near Tickencote) – the maternal grandfather of my neighbour and cousin, Sir James Wingfield of Kimbolton Castle, had been Sir James Harington of Exton.30 In all, cousin Bartholomew and I found about 40 of the first settlers.31 Mr. Gabriel Bedell (related to Mr. Kenelm Throgmorton, as I recall) from near Stonely and Mr. Matthew Scrivener, 26, son of wool magnate Ralph Scrivener32 the Older of Ipswich & of Belstead Manor (Suffolk) – were unable to come with me there and then, but agreed to join the First Supply. Young Matthew was “a good old boy” – who was to be a good restraining hand on the excesses of Presidents John Sicklemore and then John Smith in our new colony – before he tragically drowned (just as his brother Nicholas had, at Eton). And Matthew’s sister Elizabeth was to marry my cousin Harbottle Wingfield of Crowfield near Letheringham.

We wanted to leave in the autumn. I sorted many books in my house to be sent up to me at my going to Virginia, amongst them a Bible. They were sent up in a trunk to London, with diverse fruit, conserves and preserve…which I did set in Mr. Croft’s house – Richard Croft the settler’s – in Ratcliffe near Blackwall Dock. In my being in Virginia, I did understand my trunk was broken up, much lost, my sweetmeats eaten at his table, some of my books which I missed, to be seen in his hands, and whether amongst them my Bible was so embezzled or mislaid by my servants, and not sent me, I know not…33

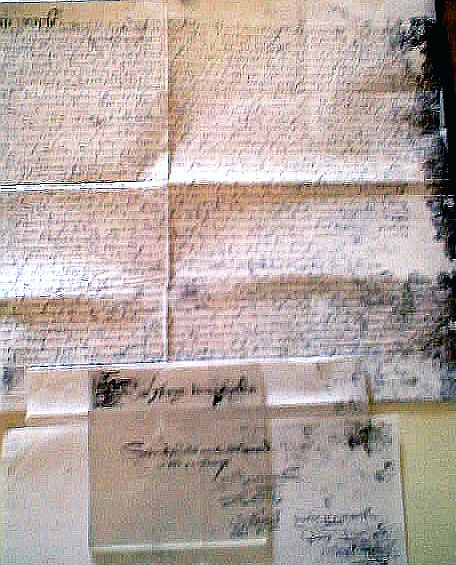

However, when we were ready to sail, we had still not raised enough ready money in our “Fund for the Support of the Colony in Virginia” to pay the bills for victuals and equipment. In the London Company I was the only adventurer (risking my money) and venturer (risking my person) to sail.34 More money was needed at once. So, as our final possible sailing date for 1606 approached, I rode the 100 miles back to Stonely and mortgaged my mansion house at Stonely, and my entire estate35 in Kimbolton, Great Stoughton, Overstowe, Netherstowe, and Pertenhall: to, of the first part – Lord Chief Justice Sir John Popham, Sir Anthony Mildmay of Apethorpe, Northants (my neighbour from my second home of Fotheringhay), Sir Richard Wingfield, the Knight Marshal of Ireland, Sir Robert Wingfield III of Upton (near Stamford, Lincs), Sir Thomas Wingfield of Letheringham (Suffolk), my neighbor Robert Throckmorton of Ellington; and of the second part – John Pickering, married to Lucy Kaye, kin of my mother Margaret, and son of Gilbert Pickering, of Titchmarsh (both next to Stonely Priory); of the third part – Sir John Hatchcross of Lincolnshire; and Gilbert Pickering of Titchmarsh (next to Stonely); and of the fourth part: Gamaliel Crews of Swaffham (Norfolk), my stepfather’s eldest son; and of the fifth part – Sir John Popham, Sir Anthony Mildmay, Sir Richard Wingfield, Sir Francis Popham (son & heir of Sir John), Sir Robert Wingfield, Sir Thomas Wingfield, Robert Throgmorton, and John Pickering. And they would receive all my rents etc in the event of my demise in Virginia or at sea.

Arranging this indenture, “The Stonely Deed”, took me much time and the document – witnessed by my brother Richard, was not signed until 17th December 1606. Thus and thus only, largely through the backing of Wingfield family money, two days later, were we able to sail – it’d be very late for planting – on 19th December from Blackwall Dock on the Thames. I sailed as I recall in the “Susan Constant” under the command of Captain Christopher Newport of the One Hand”, who was Admiral of our fleet of three little ships for the crossing.

My old friend and former fellow-prisoner, Sir Ferdinando Gorges, had taken charge of the Plymouth Company expedition as regards exploration and the furnishing of natives from Virginia as interpreters for them; and as early as August 1606 dispatched Captain Henry Challoner to explore – but those perfidious Spaniards – no longer at war with us – took him and his crew prisoner. So, Sir John Popham sent off Martin Pring to explore. Meanwhile my London Company was to settle first on that far shore.

En route to Virginia, our Admiral for the crossing, Captain Christopher Newport, erected a gallows on Nevis and nearly hanged Mr. John Smith, but eventually just placed him under restraint – not in irons – for concealing a mutiny – a very serious charge – in which Mr. Stephen Calthorpe was also involved. As I recall it was over our Captain Newport taking the longer, southern route and over – even that early – bad rations. As the chief incorporator, naturally I fully supported Captain Newport.

Having approached Virginia’s coast, on April 27th 1607 we assembled the shallop (sloop) and made the first landing and praised the Lord, naming that place Point Henry for the young heir to our gracious Lord, King James. That first day, I patrolled with Captain Christopher Newport, young Mr. George Percy (27), Mr. Gabriel Archer and two dozen men, and, returning around midnight we were assaulted by five “naturals” – people of the indigenous population. When we opened the “sealed box” we found the council commanded by the King were to be seven of us: myself, Gosnold, Newport, Ratcliffe (actually called Sicklemore), Smith, Kendall and Martin, but we other six decided to exclude Smith since he was temporarily under restraint – not in chains, but – as I recall – he had a guard and could not bear arms of course. We were to choose a President from amongst ourselves – which I believe we left until we had a settling place. Obviously how we behaved towards each other in the following couple of weeks would affect the first English election on the English soil of Virginia. I felt I could count on my young cousin Gosnold’s voice (vote) and perhaps Newport’s.

By May 12th we were some 80 miles up “King James His River” – as we named it, when Mr. Gabriel Archer, supported by Captain Bartholomew Gosnold, strongly proposed a place he called “Archer’s Hope” for our city, but I vetoed it, as not a good enough defensive position. I then found two miles upstream a good and fertile island, a truly perfect defensive position (even from the far side from the river) for our first seating place, where I could have the three ships moored right alongside the bank-side fort (I had been warned by my old friend and neighbour, Sir Ralph Lane, the late Governor of Roanoke, of the problems that he encountered by having his ships moored a mile away from their settlement). Of my selection of this low-lying island (low-lying as had been Archer’s Hope), I heard that John Smith in the following year was to describe it as “a very fit place for the erecting of a great city”. The majority of the company, including George Percy approved of my choice. As it was late, we moored there overnight.

It was now I think that we held our election and the council voted me the first President. I found, as expected (since I was the oldest, I had been named in the Charter and I had planned the expedition with my young cousin, Bartholomew Gosnold – steered by the great Mr. Hakluyt), that I was to be the first President – equipped with far-reaching powers. Although I could pass ordinances (valid only until approved or altered by the Crown), coin money, and, with the council, try civil cases and lesser criminal charges, and pass sentence or issue pardons – even for manslaughter – I had no jurisdiction over Captain Christopher Newport’s mariners (who were to stay too long, loading sassafras and while we searched for gold – eating the colony’s rations). But we had our instructions from London, and we could not build and explore without the mariners’ help. And, I discovered, I could be ousted from the Presidency by a majority vote of the council.

At dawn on Wednesday May 13th we unloaded our stores with dispatch. Then I made a Presidential oration, praising God, the King and the Prince of Wales and naming our settlement James Fort or James Town and explained why Mr. Smith was not yet on the council. Some “common kettle” food was buried in the ground for security and to keep it from going bad. Some of the Gentlemen still had a bit of tough meat or wine or salad dressing in their chests, which they had been unable to access on the voyage. That they now surely devoured at once or very soon after landing.

I divided the 104 colonists and 56 mariners into work details – using most of them on watch and ward duty, patrolling and administration. I also had a party sowing corn on two hillsides (which was in time to spring a man’s height from the ground” – reported on, I heard later, by Mr. George Percy and by “Mr. Francis Perkins of Villa Jamestown”.) and I sent out a patrol of 20 under Captain Christopher Newport – which left but around 30 for the felling of 500-600 trees for the construction of the great triangular fort of 140 yards on the river side and 100 yards for each of the other two sides, with three artillery blisters each of twenty yards circumference – the same as old George Popham was going to build for the northern colony. I supervised Captain George Kendall in this work. In the normal military manner, naturally before the palisade was in position, we had to make do with makeshift piles of trunks and brushwood for temporary defense works in case of alarms. My guards had reported one or two single naturals – local men – practicing upon opportunity.

On the Wednesday after Whitsunday, despite our guard and mastiffs, some 400 naturals36 crept up – as only they can do with such animal-like skill – and gave a very furious assault upon our half-finished fort. We just had time to stand to arms and for me to dispatch my cousin Captain Barthlomew Gosnold to the ships secured to the bank to man the sakers (artillery pieces), before I led the defense from the front with Mr. John Sicklemore, Mr. George Kendall and Mr. John Martin. The assault endured hot about an hour, but, although outnumbered two or perhaps three to one (since besides Newport, some men were out planting and patrolling), and despite losing a boy and a dozen of us being wounded including we four councillors, we drove them off in a little over an hour – carrying away their twenty or so dead. I had one arrow shot clean through my beard, yet ‘scaped hurt from it. Gosnold’s shipboard artillery caused them finally to depart. Two days later poor old Mr. Eustace Clovill was pierced by six arrows, yet managed to run into the half-finished fort to raise the alarum.

It was in the following week, the week that Opechancanough and three other chiefs offered me an Alliance against the Paspaheghs, that I decided to admit John Smith to the Council. I then prepared a Report37 for Christopher Newport to take back to the Council in London. This read:

“Within less than seven weeks we are fortified well against the Indians. We have sown good store of wheat – we have sent you a case of clapboard – we have built some houses – we have spared some to a discovery, and still as God shall enable us with a strength, we will better and better our proceedings.

Our easiest and richest commodity being sassafrass, roots were gathered up by the sailors with loss of our tools withdrawing our men from our labour. We wish they may be dealt with so that all the loss neither fall on us or them. [As I recall I refused Captain Newport’s demand that these two sentences be omitted. Unfortunately I had no jurisdiction over the sailors!] I believe [I wrote “I” to make clear to London that I as President wrote the report, even though the council all signed it!] they have thereof two tons at least, which if they scatter abroad at their pleasure will pull down our price for a long time, [so] we leave this to your wisdoms. The land would flow with milk and honey if seconded by your careful wisdom and bountiful hands. We do not persuade you to shoot one arrow to seek another, but to find them both. And we doubt not but to send them home with golden heads…

We are set down 80 miles within a river for breadth, sweetness of water, length navigable up into the country, deep and bold channel so stored with sturgeon and other sweet fish, as no man’s fortune hath ever possessed the like… The soil is most fruitful, laden with good oak, ash, walnut tree, poplar, pine, sweet woods, cedar, and others yet without names that yield gums pleasant as frankincense, and experienced amongst us for great value in healing green wounds and aches. We entreat your succours with all expedition, lest that all-devouring Spaniard lay his ravenous hands upon these gold showing mountains…

Which if we were so enabled, he shall never dare to think on. This note doth make known where our necessities do most strike us, we beseech your present relief accordingly, otherwise to our greatest and lasting griefs, we shall against our will, not will that which we most willingly would.

Captain Newport hath seen all and knoweth all; he can fully satisfy your further expectations and ease you of our tedious letters. We must humbly pray the heavenly King’s hand to bless our labours with such counsels and helps as we may further and stronger proceed in this our King’s and country’s service.

Your poor friends, Edward-Maria Wingfield, Bartholomew Gosnold …” and I then passed the report to sign next, to our new councillor, Mr. John Smith.

Captain Christopher Newport, having always his eyes and ears open to the proceedings of the colony, three or four days before his departure asked me as President, how I thought myself settled in the government. My answer was that no disturbance could endanger me, but [that] it must be wrought either by Captain Bartholomew Gosnold or Mr. Gabriel Archer; for the one (Gosnold) was strong with friends and followers (including his old Cape Cod shipmates and who had been hurt that he had not been selected as Admiral for the voyage out, or as President), and could cause upset if he would; and the other (Archer) was troubled with an ambitious spirit, and would if he could. … Captain Newport – very stupidly – gave them both knowledge of this, my opinion. June the 22nd Captain Christopher Newport returned for England – for whose good passage and safe return we made many prayers to our Almighty God.

June the 25th an Indian came to us from the great Powhatan with the word of peace – that he desired greatly our friendship, that the werowances – or chiefs – Paspahegh and Tapahanah, should be our friends, that we should sow and reap in peace, or else he would make wars upon them with us. This message fell out true, for both those werowances have ever since remained in peace with us. We rewarded the messenger with many trifles, which were great wonders to him.

The Powhatan dwelleth 10 miles from us upon the River Pamunkey, which lieth north from us. The Powhatan in the formal journal mentioned – Newport’s journal of his discoveries – (a dweller by Newport’s faults) is a werowance and under this great Powhatan – which before we knew not.

The 3rd of July seven or eight Indians presented me, as the President, a deer from the Pamunkey king, Opechancanough, a werowance desiring our friendship. They were well contented with trifles (trinkets, as presents). A little after this came a deer to me as the President from the great Powhatan. He and his messengers were pleased with the like trifles. I instituted bartering with the natives – indeed as the President at diverse times I likewise bought deer of the Indians, [and] beavers and other flesh – which we always caused to be equally divided among the colony.

About this time diverse of our men fell sick. We missed about forty before September did see us, amongst whom – on 14th August died my neighbour Ensign Jerome Alicock from a wound, and then my cousins by marriage: Stephen Calthorpe the following day and on 22nd August – the worthy and religious gentleman, Captain Bartholomew Gosnold – upon whose life stood a great part of the good success and fortune of our government and colony. Two and four days later died my cousin Edward Harington from Exton and then, I believe, my neighbour, Kellam Thogmorton from Ellington.

In my sickness time, I did easily foretell my deposing from my command. So much differed between me .. and the other – young -Councillors in managing the government of the colony.

The 7th of July Tapahanah, a werowance, [a] dweller on the Salisbury side (the south side of the James) hailed us with a word of peace. I as President with a shallop well manned went to meet him. I found him sitting on the ground, cross-legged as is their custom, with one attending him which did often say: “This is the werowance Tapahanah” – which he did likewise confirm with stroking his breast. He was well enough known, for I had seen him diverse times before. His countenance was nothing cheerful – for we had not seen him since he was in the field against us, but I would take no knowledge thereof and used him kindly, giving him a red waistcoat, which he did desire.

Tapahanah did enquire after our shipping. He received answer as before. He said his old store of corn was spent, that his new one was not at full growth by a foot; that as soon as any was ripe he would bring it – which promise he truly performed.

The – I forget the date – Mr. Kendall was put out from being of the Council, and committed to prison, for that it did manifestly appear he did practise to sow discord between me as President and the Council.

Sickness had now left us 6 able men in our town. God’s only mercy did now watch and ward for us, but as President I hid this our weakness carefully from the savages, never suffering them in all my time to come into our town.

The 6th of September Paspahegh sent us a boy that was run from us. This was the first assurance of peace with us. Besides we found them no cannibals.

The boy [had] observed the native men and women to spend the most part of the night in singing or howling, and that every morning the women carried all the little children to the river’s sides – but what they did there he did not know.

The rest of the werowances do likewise send our runaways to us home again, using them well during their being with them. So – as now – their being well rewarded at home at their return, they take little joy to travel abroad without passports.

The council demanded some larger allowance for themselves and for some sick, their favourites – which I would not yield unto without their warrants. This matter was before compounded by Captain Martin, but so nakedly as they neither knew the quantity of the store to be but for 3 weeks and a half, under the Cape Merchant’s hand (chief storekeeper’s signature). As President I prayed them further to consider the long time before we expected Captain Newport’s return, the uncertainty of his return, if God did not favour his voyage; the long time before our harvest be ripe and the doubtful (precarious) peace we had with the Indians – which they would keep no longer than opportunity served to do us mischief.

It was then therefore ordered that every meal of fish or flesh should excuse (omit) the allowance for porridge – both against (for) the sick and the whole (the well). The council therefore sitting again upon this proposition, instructed in the former reasons and order, did not think fit to break the former order by enlarging their allowance, as will appear by the most voices under their hands (votes). Now was the common store of oil, vinegar, sack (sherry), and aquavit all spent, saving two gallons each – the sack for the communion table, the rest for extremities (emergencies) as might befall us – which I had made known only to Captain Bartholomew Gosnold – of which course he liked well. The vessels were therefore bunged up. When Mr. Gosnold was dead, I did acquaint the rest of the council with (about) the said remnant – but, Lord, how they longed for to sup up that little remnant! – for they had now emptied all their own bottles, and all other that they could smell out.

A little while after this the council did again fall upon me for some better (food) allowance for themselves and some few sick, their privates (servants). I protested I would not be partial, but if one had [persuaded] anything of me, every man should have his own portion according to his place. Nevertheless, that upon their warrants (authorisation and support), I would deliver what pleased them to demand. If as President I had at that time enlarged the portion according to their request, without doubt in very short time I had (would have) starved the whole colony. I would not join with them therefore in such ignorant murder without their own warrant (unanimous support).

Well seeing to what end their impatience would grow, I desired them earnestly and often (several) times to bestow the Presidency among themselves (elect one of themselves as President), [saying] that I would [resign and] obey a private man as well as he could command. But they refused to discharge me of the place (office), saying they must not do it, for that (because) I did His Majesty good service in it. In this meantime the Indians did daily relieve us with corn and flesh (meat) – that in three weeks I had reared up 20 men able to work. For, as this store increased, I mended (replenished) the common pot (the colony’s food supply) I had laid up, besides beforehand (including earlier) provision for 3 weeks’ wheat.

By this time the council had fully plotted to depose me as President and had drawn [up] certain articles in writing among themselves, and took their oaths upon the evangelists to observe them. The effect whereof was, first, to depose me as the then President [and] to make Mr. John Ratcliffe aka Sicklemore the next President; not to depose the one the other (one another); not to take me into [the] council again; not to take Mr. Gabriel Archer into the council, or any other, without the consent of every one of them. To this they had subscribed – as out of their own mouths at several times it was easily gathered. Thus they had forsaken what His Majesty’s Government set us down (set down for us) in our “Instructions [by Way of Advice]”– and made it a Triumvirate (a 3-man government).

It seemeth that Mr. Archer was nothing acquainted with these articles – though all the rest that were preferred against me crept out of his notes and commentaries. Yet it pleased God to cast him into the same disgrace and pit that he prepared for another – as will appear hereafter.

The 10th of September Mr. Ratcliffe, Mr. Smith and Mr. Martin came to my tent with a warrant subscribed under their hands to depose me as President, saying they thought me very unworthy either to be President or of the council, and therefore discharged me of both.

I answered them that they had eased me of a great deal of care and trouble, that long since I had at diverse times preferred them the place [of President] at an easier rate (in an easier manner); and further that the President ought to be removed, as appeareth in His Majesty’s Instructions for our government, by the greater number of 13 councillors’ voices (votes), but they were but three; and [I] therefore wished them to proceed advisedly. But they told me if they did me wrong, they must answer for it. Then as the deposed President, I said: “I am at your pleasure. Dispose of me as you will without further “garboils” (uproar).

I will now say what followed in my own name and give the new President his title. I shall be the briefer, being thus discharged. I was committed to a sergeant and sent to the pinnace – the 20-ton “Discovery” – but I was answered with “If they did me wrong they must answer for it.”

The 11th Of September I was sent for to come before the President and his council upon their court day. They had now made Mr. Archer Recorder of Virginia. The President made a speech to the colony, that he thought it fit to acquaint them [with] why I was deposed. I am now forced to deal with frivolous trifles, that pour grave and worthy council may the better strike those veins where the corrupt blood lieth and that they may see in what manner of government the hope of the colony now travaileth.

First Master President said that I had denied him a penny whittle (pocket knife), a chicken, a spoonful of beer and served him with foul corn – and with that pulled some grain out of a bag, showing it to the company. Then start up Mr. Smith, and said that I had told him plainly how he lied; and that I said – though we were equal there – yet if he were in England, he (Smith) would think scorn his man (-servant) were my companion.

Mr. Martin followed with – he reporteth that: “He do slack the service in the colony, and do nothing but tend his pot, spit and oven, that he hath starved my son and denied him a spoonful of beer. I have friends in England [that] shall be revenged on him if he ever come in (to) London.”

I asked Mr. President if I should answer these complaints and whether he ought else to charge me withal. With that he pulled out a paper notebook, loaded with articles against me and gave them to Mr. Archer to read.

I told Mr. President and the council that, by The Instructions for our government, our proceedings ought to be verbal and I was there ready to answer – but they said they would proceed in that order. I desired a copy of the articles, and time given me to answer them likewise by writing – but that would not be granted. I bade them then please themselves. Mr. Archer then read some of the articles – when, on the sudden, Mr. President said: “Stay, stay! We know not whether he will abide by our judgement, or whether he will appeal to the king”, saying to me, “How say you? Will you appeal to the King, or no?”

I apprehended (seized on) presently that God’s mercy had opened me a way, through their ignorance, to escape their malice, for I never knew [before] how I might demand an appeal. Besides I had a secret knowledge how they had forejudged me to pay fivefold for anything that came to my hands, whereof I could not discharge myself by writing; and that I should lie in prison until I had paid it.

The cape merchant had delivered me our merchandise without any note of the particulars under my hand, for (he) himself had received them in gross. I likewise as occasion moved me, spent them in trade or by gift (as a gift) amongst the Indians. So likewise did Captain Newport take of them what he thought good (suitable), when he went to discover the King’s River – without any note of his hand (signature &c) mentioning the certainty; and disposed of them as was fit for him. Of these likewise I could make no account – only I was well assured I had never bestowed the value of three penny whittles (knives) to my own use nor to the private use of any other. For I never carried any favourite over with me or entertained any there. I was all [for] one and one to all.

Upon these considerations I answered Mr. President and the council, that His Majesty’s hands were full of mercy and that I did appeal to that mercy. They then committed me prisoner again to the master of the pinnace with these words: “Look to him well: he is now the King’s prisoner.”

Then Mr. Archer pulled out of his bosom another notebook full of articles against me, desiring that he might read them in the name of the colony. I said I stood there ready to answer any man’s complaint whom I had wronged – BUT NOT ONE MAN SPOKE ONE WORD AGAINST ME. Then was he willed to read his book – whereof I complained. But I was still answered [that] if they do me wrong, they must answer for it. I have forgotten most of the articles, they were so slight – yet he (Archer) glorieth much in his penwork (paperwork). I knew well the last; and a speech that he then made savoured well of a mutiny – for he desired well that I might lie prisoner in the town, lest both he and others of the colony should not give such obedience to their command as they ought to do – which goodly speech of his they easily swallowed.

But it was usual and natural to this honest gent, Mr. Gabriel Archer, to be always hatching of some mutiny in my time. He might have appeared the author of 3 several mutinies. And he – as Mr. George Percy sent me word – had bought some witnesses’ hands against me to (on) diverse articles with Indian cakes (which was no great matter to do after my deposal and considering their hunger), persuasions and threats. At another time he feared not to say openly and in the presence of one of the council, that, if they had not deposed me when they did, he had (would have) gotten twenty others to himself which should have deposed me. But this speech of his was likewise easily digested.

Mr. Crofts feared not to say that if others would join with him, he would pull me out of my seat and out of my skin too. Others would say (whose names I spare) that, unless I would amend their (food) allowance, they would be their own carvers. For these mutinous speeches I rebuked them openly and proceeded no further against them – considering therein men’s lives in the King’s service there. One of the council was very earnest with me to take a guard about me. I answered him, I would [have] no guard but God’s love and my own innocence. In all these disorders was Mr. Archer a ringleader.

When Mr. President and Mr. Archer had made an end of their articles above mentioned, I was again sent prisoner to the pinnace; and Mr. Kendall, taking (being taken) from thence, had his liberty, but might not carry arms.

All this happening while the savages brought to the town such corn and flesh as they could spare. Paspahegh, by Tappahanna’s mediation, was taken into friendship with us. The councillors, Mr. John Smith especially, traded up and down the river with the Indians for corn, which relieved the colony well.

As I understand by a report, I am much charged with starving the colony. I did always give every man his allowance faithfully, both of corn, oil and aquavit, &c, as was by the council proportioned; neither was it bettered after my time, until – towards the end of March (1608) – a biscuit was allowed to every working man for his breakfast, by means of the provision brought us by Captain Newport (as will appear hereafter). It is further said that I did banquet and riot. I never had but one squirrel roasted, whereof I gave a part to Mr. John Ratcliffe (Sicklemore), then sick, yet was that squirrel given me. I did never heat a flesh pot (meat cooking pot) except when the common pot was so used likewise. Yet how often Mr. President Ratcliffe’s and the councillors’ spits have night and day been endangered to break their backs – so laden with swans, geese, ducks, &c! How many times their flesh pots have swelled, [which] many hungry eyes did behold to their great longing! And what great thieves and thieving hath been in the common store since my time I doubt not, but [that] is already made known to His Majesty’s council for Virginia.

The 17th day of September I was sent for to the court to answer a complaint exhibited against me by Mr. Jehu Robinson, for that when I was President I did say [that] he with others had consented with others to run away with the shallop to Newfoundland. At another time, I must answer Mr. John Smith for that I had said he did conceal a mutiny. Strange that he did not invent that earlier. I told Mr. Recorder Archer those words would bear no actions, that one of the causes was done without (outside) the limits mentioned in the Patent granted to us; and [I] therefore prayed Mr. President that I ought not to be lugged (lumbered) with these disgraces and troubles – but he did wear no other eyes and ears than grew on Mr. Archer’s head.

The jury gave (awarded) the one of them £100 and the other £200 damages for slander. Then Mr. Recorder did very learnedly comfort me, that if I had wrong (been wronged), I might bring my writ of error in London – whereat I smiled.

Seeing their law so speedy and cheap, I desired justice for a copper kettle Mr. Richard Crofts did detain from me. He said I had given it to him. I did bid him bring proof for that. He confessed he had no proof. Then Mr. President did ask me if I would be sworn (would swear) I did not give it to him. I said I knew no cause why to swear for mine own [property]. He asked Mr. Crofts if he would make oath I did give it to him – which oath he took and [thereby] won my kettle from me. And that was – in that place and time – worth half his weight in gold. Yet I did understand afterwards from Mr. George Percy that he [Mr. Archer] would have given John Capper – a hatter, as I recall – the one half of the kettle to have taken the oath for him, but he (Capper) would have no copper at that price – by bearing false witness against me.

I told Mr. President that I had not known the like law, and prayed that they would be more sparing of law until we had more wit (wisdom) or wealth; that laws were good spies in a populous, peaceable and plentiful country – where they did make the good men better and stayed the bad [men] from being worse. Yet we were so poor as they did but rob us of time that might be better employed in [the] service of the colony.

One day the President did beat James Read, the smith. The smith struck him [back] again. For this he was condemned to be hanged, but, before he was tanned with the leather [strap], he desired to speak to the President in private, to whom he accused Mr. Kendall of a mutiny – of attempting to sail to Newfoundland – and so [Read] escaped himself. What indictment Mr. Recorder framed against the smith I know not; but I know it is familiar (commonplace) for the President, councillors and other officers to beat men at their pleasure (leisure). One lieth sick till death, another walketh lame, a third crieth out of all his bones – which miseries they do take upon their consciences to come to them by this their alms of beating. Were this whipping, lawing (“interpretation” of the law), beating and hanging, known [about] in England, I fear it would drive many well affected minds from this honourable action in Virginia.

This smith (James Read) coming on board the pinnace with some others about some business 2 or 3 days before his arraignment, brought me commendations from Mr. George Percy, Mr. John Waller, Mr. George Kendall and some others, saying they would be glad to see me on shore. I answered him [that] they were honest gentlemen and had carried themselves obediently to their governors. I prayed God that they did not think of any ill thing unworthy [of] themselves. I added further that upon Sunday, if the weather were fair, I would be at the sermon. Lastly, I said that I – aged 57 – was so sickly, starved, [and] lame and did lie so cold and wet in the pinnace, as I would [have to be] dragged thither, before I would go there any more. Sunday proved not fair [so] I went not to the sermon.

One day Mr. George Kendall was executed – being shot to death for a mutiny. In the arrest of his judgment, he alleged to the President that his [the President’s] name was Sicklemore – not Ratcliffe – and so he had no authority to pronounce judgement. [So] then Mr. John Martin pronounced judgement.

Somewhat before this time, the President and council had sent for the keys of my coffers (chests) supposing that I had some writings concerning the colony. I requested that the clerk of the council might see what they took out of my coffers, but they would not suffer him or any other [to watch them]. Under cover hereof (of this) they took my books of account and all my notes that concerned the expenses of the colony and instructions of (in) the cape merchant’s (chief storeman Mr. Thomas Studley’s) hand of the store of provision, diverse other books and trifles of my own proper (personal) goods – which I could never recover. Thus I was made [a] good prize on all sides.

On another day the President commanded me to come on shore – which I refused, as [I was] not rightfully deposed, and desired that I might speak to him and the council in the presence of 10 of the best sort of gent. With (after) much entreaty, some of them were sent for. Then I told them I was determined to go to England to acquaint our council there with our weaknesses. I said further, their laws and government was such that I had no joy to live under them any longer, that I did much dislike their triumvirate having forsaken His Majesty’s “Instructions for our Government”, and (I) therefore prayed there might be more made of (elected to) the council. I further said that I desired not to go to England, if either Mr. President Sicklemore (aka Ratcliffe) or Mr. Gabriel Archer would go, but if the action was (thus) given over, I was willing to take my fortune with the colony, and [I] did also proffer to furnish them with £100 towards fetching home the colony. They (the triumvirate) did not like none (any) of my offers, but made diverse shot at me in the pinnace. Seeing their resolution, I went ashore to them – where, after I had stayed a while in conference, and there was much ado to have the pinnace go to England and after many debatings pro and contra it was resolved to stay a further resolution38 – before they sent me to the pinnace again.

The 10th of December Mr. John Smith went up the river of the Chickahominies to trade for corn. He was desirous to see the head of that river. And when it was not possible with the shallop he hired a canoe and an Indian to carry him up further. The river the higher (up) grew worse and worse. Then he went on shore with his guide and left Mr. Jehu Robinson and [carpenter] Thomas Emry, two of our men, in the canoe – which (men) were presently slain by the Indians (Pamunkey’s men) and he himself was taken prisoner. And, by the means of his guide his life was saved. And Pamunkey, having him prisoner, carried him to his neighboring werowances (chiefs) to see if any of them knew him for (as) one of those which two or three years before us had been in a river amongst them [to the] northward and [who] had taken away some Indians by force. At last, he (Pamunkey) brought him before the great Powhatan (of whom we had no knowledge) – who sent him home to our town the 8th of January. (It was only last year – for the first time – that Mr. John Smith garnished the story of his capture, with his life being saved by a daughter of the chief in some strange ceremony – maybe an adoption ceremony, suspiciously exactly the same as Hakluyt had it in the story of Chief Ucita’s daughter Ulalah saving a conquistador in La Florida all those years ago). This Virginian child, called Matoaka or Pocahontas, they told me (I never met her), – who last year as wife of Mr. John Rolfe, died tragically at Gravesend in Kent – was, back then, apparently but about 7 to 9 years old.39

During Mr. Smith’s absence the President did swear Mr. Gabriel Archer [as] one of the council – [which was] contrary to his oath taken in the Articles and agreed upon between themselves (before spoken of) and contrary to the King’s Instructions and contrary to Mr. Martin’s consent. Whereas there were no more but the President and Mr. John Martin on the council.

John Smith again due to be hanged

Being settled in his authority, Mr. Gabriel Archer, sought how to call Mr. John Smith’s life into question, and had indicted him upon a chapter in Leviticus, for the death of the two men. He (Smith) had his trial the same day as his return, and I believe his hanging [was to be on] the same or the next day, so speedy is our law there [in Virginia]. But to our unspeakable comfort, it pleased God to send Captain Christopher Newport unto us the same evening – whose arrival saved Mr. Smith’s life and mine, because he (Newport) took me out of the pinnace and gave me leave to lie (live) in the town. I had been so cold and sick in the pinnace, I believe I would soon have died. Also by his coming was prevented a parliament, which the new councillor, Mr. Recorder, intended them to summon. Thus error begat error. Captain Newport having landed, lodged and refreshed his men, employed some of them about [in constructing] a fair storehouse, others about a stove and his mariners about a church – all [of] which works they finished cheerfully and in [a] short time.

The 7th of January [1608] our town was almost quite burned, with all our apparel and provisions, but Captain Newport healed our wants to our great comforts out of the great plenty sent us by the provident and loving care of our worthy – and [indeed] most worthy – council in London.

This vigilant captain, [Christopher Newport], slacking no opportunity that might advance the company upon the former works, took Mr. John Smith and Mr. Matthew Scrivener, (aged 28), whose sister Elizabeth married my cousin, Harbottle Wingfield of Crowfield40 near Letheringham and Otley, (another councillor of Virginia, upon whose discretion lived (depended) a great hope of the action), went [off] to discover (explore) the River Pamunkey, on the further side whereof dwelleth the Great Powhatan and to trade with him for corn. This river lieth north from us and runneth east and west. I have nothing but by relation – as related to me – of that matter, and therefore dare not make any discourse thereof, lest I might wrong the great dessert which Captain Newport’s love to (of) the action hath deserved – especially himself being present [in 1608 in London] and best able to give satisfaction [a satisfactory account] thereof . I will hasten [my account] therefore to his return.

The 9th of March he [Newport] returned to Jamestown with his pinnace well laden with corn, wheat, beans and peas, to our great comfort and his worthy commendations. By this time the council and the captain (Newport), having intentively looked into the carriage (behaviour) of the councillors and other officers, removed some officers out of the store and Captain Gabriel Archer – a councillor, whose insolence did look upon that [a] little himself with great sighted spectacles, derogating from others’ merits by spewing out his venomous libels and infamous chronicles upon them – as doth appear in his own handwriting. For which other worse tricks he had not (Archer would not have) escaped the halter (noose), but that (had not) Captain Newport interposed his advice to the contrary – that is that the council should not hang Mr. Archer.

Captain Newport, having now dispatched all his business [loading his ship with supposed gold dust] and “set the clock on a true course” – if so (if only) the council will keep it, prepared himself for England upon the 10th day of April; and arrived at Blackwall – with me – on Sunday the 21st May 1608. I humbly crave some patience to answer many scandals and imputations – which malice, more than malice – hath scattered upon my name, and those frivolous three names objected against me by the President (Sickelmore) and council (Smith and Martin). And though “nil conscire sibi” (an individual being unaware of his own guilt) be the only mask that can well cover my blushes, yet do I not doubt, but that this my apology shall easily wipe them away.

It was noised abroad (suggested) – in Virginia – that (1) I combined with the Spaniards to the destruction of the colony, (2) that I am an atheist because I did not carry a Bible with me and because I did forbid the preacer to preach and (3) that I did affect a kingdom.

(1) I confess that I have always admired any noble virtue and prowess – as well in the Spaniards as in other nations, but naturally I have always distrusted and disliked their “neighbourhood” (company) – indeed you will remember I spent several years fighting the all-devouring Spaniard in the Low Countries in the 1580s, and 20 years before cousin Gosnold and I founded Jamestown, I was with Sir Ferdinando Gorges captured and – initially – ransomed by them.

(2) As I said earlier, I sorted many books in my house to be sent up [to London] to me at my going to Virginia, amongst them a Bible. They were sent me in a trunk to London with diverse fruit, conserves and preserves, which I did set in Mr. Richard Croft’s house in Ratcliff (convenient for Blackwall Dock). On my being in Virginia I did understand [learn that] my trunk was broken up, much lost, my sweetmeats eaten at his (Croft’s) table [and] some of my books which I missed [were] to be seen in his hands; and whether amongst them my Bible was so embezzled – or [else] mislaid by my servants and not sent [on to] me – I know not as yet.

Two or three Sunday mornings [in Jamestown] the Indians gave us alarms. By the time that they were answered with long stands to arms to repel a possible attack, [and] the place (area) round about us well discovered (investigated), (the rest of) our divine service ended (had to be cut short, since) the day was far spent. The preacher did ask me if it was my pleasure to have a sermon – [and] he said he was prepared for it. I made answer that our men were weary and hungry, and that he did (could) see the day far past. For at other times he never made such a question, but the service finished, he began his sermon. And (therefore) if it pleased him, we would spare him [the sermon] till some other time. I never failed to take such notes by [the] writing out of his doctrine, as [far] as my capacity could comprehend – unless some rainy day hindered my endeavour (in trying to write).

(3) My mind never swelled with such impossible mountebank humours (a boastful frame of mind), as could make me affect any other kingdom than the kingdom of heaven.

As truly as God liveth I gave an old man, then the keeper of the private store, 2 glasses of salad oil which I brought with me out from England for my private use and asked him to bury it in the ground – for I feared the great heat would spoil it. Whatsoever was more I did never consent unto it and – as truly as was protested unto me – that all the remainder mentioned, of the oil, wine &c, which the (new) president received of me when I was deposed: they themselves poured it into their own bellies.

To the President and council’s objections, I say that I do know courtesy and civility become a governor. No penny whittle (pocket knife) was asked (of) me, but (rather) a knife – whereof I had no spare one [because] the Indians had long [since] stolen mine. Of chickens I never did eat but one – and that in my sickness. (Mr. Ratcliff had before that tasted 4 or 5). I had by my own housewifery bred above 37 (and the most part of them (bred) of my own poultry (from Stonely, as I recall, as opposed to those we traded for in the Caribbees (Caribbean) – of all which at my coming away I did not see three living. I never denied beer [to] him (Ratcliffe) or any other [man] when we had it. The corn was the same we all lived upon.

Mr. Smith, in our time of hunger had spread a rumour in the colony that I did feast myself and my servants out of the common store – with intent, as I gathered, to have stirred up the discontented company against me. I told him privately in Mr. Gosnold’s tent that indeed I had caused half a pint of peas to be sodden with a piece of pork of my own provision (ration) for a poor old man, which in his sickness (whereof he died) he much desired; and [I] said that if out of his malice he had given it out otherwise, that he did tell a lie. It was proved to his face that he begged in Ireland, like a rogue without a licence. To such I would not my name should be a companion. As I recall , this was when he begged a company in Wingfield’s Regiment, off my Irish cousin, Sir Richard Wingfield, to go on the Cadiz Raid41 of 1596 – when he did not even know him.

Mr. Martin’s pains during my command (presidency): [he] never stirred out of our town ten score (paces). And it is well known how slack he was in his watchkeeping (guard duties) and other duties. I never defrauded his son of anything of his own allowance, but gave him above it. I believe their disdainful usage and threats which they many times gave me, would have pulled some distempered (angry) speeches out of far greater patience than mine. Yet shall not any revenging humour (feeling) in me befoul my record with their base names and and lives here and there. I did visit Mr. George Percy, Mr. William Bruster, Mr. Dru Pickhouse, Mr. Jerome Alicock, old Short the bricklayer, and diverse others at several times. I never miscalled at (abused) a gent at any time.

Concerning my deposing from my place as President I can prove that Mr. Ratcliffe said, if I used (treated) him well in his sickness (wherein I find myself not guilty of the contrary [behaviour], I had never been deposed.

Mr. Smith said, [that] if it had not been for Mr. Archer, I had never been deposed. Since his (Archer) being here in the town, he (Archer) hath said that he told the President and council that they were frivolus objections that they had collected against me, and that they had not done well to depose me. Yet, in my conscience, I do believe him [to be] the first and only practiser in these practices. Mr. Archer’s quarrel with me was because he had not the choice of the place for our plantation, because I disliked his lying out of our town in the pinnace, [and] because I would not swear him (as one) of the council for Virginia – which neither I could do nor he deserve. He died in Virginia in 1609 or 1610.

Mr. Smith’s quarrel [with me was] because his name was mentioned in the intended (planned) mutiny by Calthorpe. Thomas Wootton, the surgeon [was against me] because I would not subscribe to a warrant (which he had gotten drawn [up]) to the Treasurer of Virginia, to deliver him money to furnish him with drugs and other necessaries; and because I disallowed his living in the pinnace, having (because we had) many of our men lying sick and wounded in the town, to whose dressings by that means [- living in the pinnace-] he slacked his attendance [on them].

Of these same men Captain Gosnold gave me warning, disliking much their dispositions, and assured me that they would lay hold of me if they could, and peradventure (perhaps) many, BECAUSE I HELD (KEPT) THEM TO WATCHING, WARDING (GUARDING) AND WORKING, and [he warned me of] the colony generally, because I would not give my consent [not] to starve them – that is that I refused to increase the food ration before our crops were ready, in case Captain Christopher Newport was late in returning from England or indeed failed to return at all. I cannot rack one word or thought from myself touching my carriage (behaviour) in Virginia – other than [that that] is here set down. Clearly my tough – perhaps harsh – military discipline of tight ration controls and incessant guard and work details was more than those unused in their past lives to the rigours of a military life – those lesser spirits or slacker settlers – could stomach, especially in that most oppressive summer heat and drought and ever-present fear of attack by the naturals. But, all things being considered, they were brave men to sail with our founding expedition in the first place; and the settlement was, despite our wranglings, a joint undertaking, a team effort. Mr. Richard Hakluyt had it, that whenever food was short amongst the Spanish and French in their similar endeavours, the same occurred: the deposing of the adelantado or President. My two successors were also deposed, and Mr. John Smith too was sent home to answer questions about his presidency.

If I may at the last presume upon your favours, I am an humble suitor that your own love of truth will vouchsafe to relieve me from all false aspersions happening since I embarked me into this affair of Virginia. For other objections… I have learned to despise the popular verdict of the vulgar. I ever cheered myself with a confidence in the wisdom of grave, judicious senators and was never dismayed in all my service by any sinister event, though I bethought me of the hard beginnings, which in former ages betided those worthy spirits that planted the greatest monarchies in Asia and Europe, wherein I observed rather the troubles of Moses and Aaron with others of like history; then that venomous brood of Cadmus, who in Greek mythology fought each the other of their comrades, imagining them to be the enemy, rather than the drought; or that harmony in the sweet consent of Amphion. And when with the former, I had considered that even the brethren at their plantation of the Roman Empire, were not free from mortal hatred and intestine garboil (domestic tumult); like wise that both the Spanish and English records are guilty of like factions – like in La Florida and like I had at Jamestown – it made me more vigilant in the avoiding thereof. And I protest [that] my greatest contention was to prevent contention, and [that] my chiefest endeavour [was] to preserve the lives of others – though with great hazard to my own – for I never desired to enamel my name with blood.

I did so faithfully betroth my best endeavours to this noble enterprise, as my carriage (comportment) might endure no suspicion. I never turned my face from danger, or hid my hands from labour, so watchful a sentinel stood myself [sentinel] to myself.

On my return from Virginia, after clearing my name with the council, I proceeded to recruit more backers for the Jamestown venture – amongst whom, as I recall, were the following of my friends, relations, neighbours and acquaintances: Bacon, Bagenall, Bedell, Bingham, Blount, Brewster, Brudenell, Carew, Cecil, Clinton, Cope, Cotton, Cromwell, Danby, Drury, Ferrar, Fleetwood, Gerrard, Gilbert, Hunt, Jacob, Knowles, Lee, Mildmay (my immediate neighbour at Fotheringhay), Montagu (they purchased Kimbolton), Morgan, Quarles, Ratcliffe, Rich, St.John, Styles, Throckmorton, Vere, Wentorth, West (Lord de la Warr), White, Willoughby, Wilson, Winch, Winter, Winwood and Wroth.42 I have £88 in stocks43 in the Virginia Company, a huge sum – which I may bequeath to my third cousin, an Esquire of the Body to His Majesty, Richard Wingfield of Southminster in Essex44 – WHO SEEMS TO BE SHOWING A GREAT INTEREST in the Virginia Company of London. I am hoping that he and Robert, the 11-year-old son of my Stonely neighbours, Richard Throckmorton of Ellington & his wife Alice nee Bedell, will carry on my torch.

On a recent visit to London to the Virginia Company, I was proud to see myself listed as one of the major backers in “The Declaration of Supplies intended to be sent to Virginia in 1620” – this very year.

Last year I paid off my 1606 mortgage on my Stonely properties,44 but I may yet have to sell Stonely to the Montagus – on condition that I can be buried in the chapel there. When I was President at Jamestown I was only 57. I always was a tough old soldier, and Almighty God in his wisdom has seen fit to spare me to reach my present “3 score years and 10” (70).

I rejoice that my travails and dangers have done somewhat for the behoof of Jerusalem (the benefit of Christianity) in Virginia. If it be objected [to] as my oversight (error) to put myself amongst such men, I can say for myself, there were not any other for our consort. As in any other of His Highness’s (His Majesty’s) designs, according to my bounden duty with the utmost of my poor talent, I could not forsake the enterprise of opening so glorious a kingdom unto the King, wherein (in which enterprise) I was – after 1608 – ever most ready to bestow the poor remainder of my days

God be with you and with all who settle in Virginia!

Jocelyn R.Wingfield (b.1937, Northampton, UK) Major (retired)

Historian & International Vice-President, The Wingfield Family Society

Biographer of President Edward-Maria Wingfield

12th greats-grandson of Edward-Maria Wingfield’s great uncle Lewis Wingfield

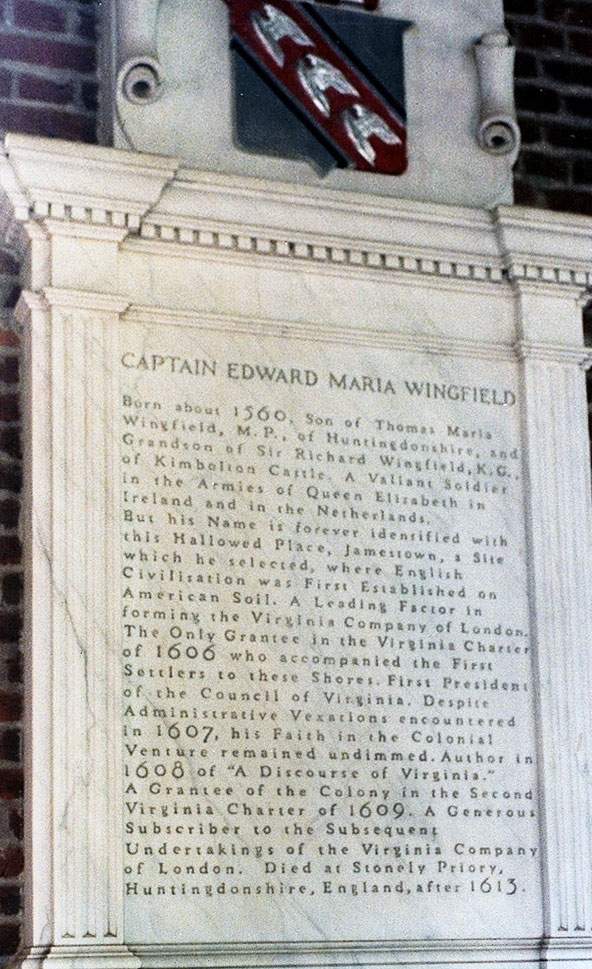

The Jamestown Church Memorial

The Jamestown Church Memorial

to Jamestown’s first President (1607) Captain Edward-Maria Wingfield

President in the first four vital months

Constructor of the great fort in a month and a day

Initiator of bartering & of peace with the locals

Planter of the first crops

One of the Virginia Company’s biggest stockholders

Text of Jamestown Church Monument reads:

CAPTAIN EDWARD MARIA WINGFIELD

Born about 1560, Son of Thomas Maria Wingfield, M.P, of Huntingdonshire, and Grandson of Sir Richard Wingfield, K.G, of Kimbolton Castle. A Valiant Soldier in Ireland and in the Netherlands.

But his Name is forever identified with this Hallowed Place, Jamestown, a Site which he selected, where English Civilization was First Established on American soil. A Leading Factor in forming the Virginia Company of London of 1606, who accompanied the First settlers to these Shores. First President of the Council of Virginia. Despite Administrative Vexations encountered in 1607, his Faith in the Colonial Venture remained undimmed. Author in 1606 of “A Discourse of Virginia”. A Grantee of the Colony in the Second Virginia Charter of 1609. A Generous Subscriber to the Subsequent Undertakings of the Virginia Company of London. Died at Stonely Priory, Huntingdonshire, England, after 1613.

(All sources – unless noted to the contrary – were published in London)

ADOV = Edward-Maria Wingfield, A Discourse of Virginia, (1608), ed. By Charles Deane, Boston, MA, 1860. DNB = (British Dictionary of Biography). VTF = Jocelyn R Wingfield, Virginia’s True Founder, Edward-Maria Wingfield & His Times, 1550-c.1614, Wingfield Family Society, Athens, GA, 1993, 343 pages (including Edward-Maria Wingfield’s “A Discourse of Virginia” c.1608, first published Boston, MA, 1860) & 104 pages of detailed source notes, bibliography and indexes. [ISBN 0-937543-04-7. Registration # TX 3 628 105 Jul 09 1993. Available in many big US libraries, US universities, Jamestown Society, VA, Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities, Jamestown, VA; British Library. WFS = Wingfield Family Society].

1 Date of birth in 1550. E150/102, p.3, Exchequer Copy (English), Lists & Indexes XXIII, PRO Kew, copy of 142/111 p.81, 1557 (Latin), Chancery Copy of Inquisition Post-Mortems etc, Series II, Vol.III, 4&5 Philip & Mary [1556-57 & 1557-58]: “Thomas Mary Wingfield died 15 August last past and Edward Wingfield is his proper son and heir and that he is of the age of seven years at the time this inquisition was taken”. (In VCH Hunts, Vol. III, p. 81, London, 1936, eds. Granville Proby & Inskip Ladds quote two incorrect sources).

2 Ped. of Crews of Fodringey , 1884, p.16; Visitation of Devon, Crews of Morchard, pp.256-257; Vis. of Norfolk, 1563, 1564,1589,1613; Cal. of Feet of Fines, Hunts, p.143; Harl. MS 1171 f.23b.

3 W.A. Copinger, Manors of Suffolk, 1909, III, p.337.

4 VTF, p.30.

5 DNB.

6 Carew MSS, Eliz., 14 Sep.1586, series 15 & 16 (vol.618, p.36a) q. in VTF, pp.45-46.

7 Cal.S.P., 1586.

8 J.Bridges, Northamptonshire, 1791, II, p.68; Vis. Hunts 1563, 1589, 1613; Harl. MS 1552, ink f.196b q. in VTF, p.357.

9 CSP (Dom) Eliz., vol.216 #6, p.49; VTF, p.49.

10 C.R.Markham, The Fighting Veres, 1888, p.128-133 q. in VTF pp.66-70.

11 Galba D1 Cotton f.133 9p.142), British Library; VTF, pp.363-376.

12 Carew papers, Cal. of 1615-1624, 1629 (ed. by J.S.Brewer & W.Bullen, 1867-73), II, p.128.

13 DNB sub Lane, Ralph.

14 S.& E. Usherwood, The Counter Armada, 1596, 1987, p.26.

15 VTF, p.104. Communication to the author by the family, 1986.

16 John Stratford, From Churchyard to Castle, the History of Kimbolton School, 2000, pp.10-14; VTF, p.130.

17 CSP Ireand, IV, pp.241, 278-279.

18 Gosnold Pedigree held at Otley Hall, Suffolk; VTF, pp.277, 405 n.38.

19 DNB, sub Lane, Ralph q. in VTF, p.94.

20 F.W. Popham, A West Country Family: the Pophams, from 1150, Gateshead, 1976, pp.41-51; VTF, pp.20, 55, 226.

21 A.Brown, The Genesis of the United States, 1964, II, p.1049; H.C. Porter, The Inconstant Savage, 1979, p.272.

22 The Charters, printed in London, 1766, in the Bancroft Collection, New York Public Library, q. in M.P.Andrews, Soul of a Nation, New York, 1943, p.46.

23 ADOV, 1608, q. in VTF, pp.163 & 342 & in Arber & Bradley, Travels & Works, Edinburgh, 1910, I, p.xci.

24 WM, p.7. Of Camberwell, just southwest of London.

25 Copinger, ibid., I, p.222 q. in VTF, p.209.

26 VTF, pp.174, 380 n.48. Perhaps because of the mutiny (?), Stephen is unidentifiable in Rev. H.J. Lee-Warner, Calthorpe Pedigrees, Norfolk & Norwich Archaeological Society, no date. (?post-1880), pp.2, 3,11-14. Christopher Calthorpe emigrated in 1622 from the next village to mine, Cockthorpe in Norfolk, to New Poquoson, Virginia.. They were flourishing in Nottoway, IOW County and Charles parish VA in the 1730s and proud of their name. [P. Palgrave-Moore, Norfolk Pedigrees, Part Five, p.31-33].

27 Research of William Gann, WFS, q. in my Letters & Diaries, WFS, 1998, pp.203-204.; The Compendium of American Genealogy, Immigrant Ancestors, sub Dade, Maj. Francis, p.24.

28 Vis. Northamptonshire, 1618-19, pp.60-61 & Northamptonshire Marriage Bonds, 1584; IGI, pp.2333 (Northamptonshire) 11781 & 11782 (Staffordshire) & 48495-48500 (London); Vis. Northamptonshire, 1681, p.161 – all q. in WFS Newsletter, vol.xii, #2, pp.11, 17-18.

29 Burke’s Peerage, 1935, sub Throckmorton of Ellington and Virginia, q. in VTF, p.261 n.23.

30 WM, pp.6-7. William M. Kelso & Beverly A.Straube’s Jamestown Rediscovery VI, 2000, where “Elton” at p.4 #26 should read “Exton”.

31 P.L.Barbour, The 3 Worlds of John Smith, 1964, pp.105-106.

32 R.Allen Brown,ed., Suffolk Chevrons, VII and Philippa Brown, ed., Sibton Abbey, Cartulaires & Charters, ISSN 0261-99370 and A.H.Denney, Rector of Trimley St.Mary (Suffolk), Sibton Abbey Estate Selected Documents 1325-1509, vol. II, 1960, all Suffolk Record Society, – all sources for the illuminated heraldic Pedigree of the Scrivener Family of Sibton Abbey & Belstead, Suffolk, property of Mr. John Levitt-Scrivener of The Abbey, Peasenhall, Suffolk, q. in VTF, pp.146 & 153.

33 ADOV, ibid (see note 23), p.lxxxviii.

34 A. Brown, Genesis of the U.S., II, p.1055.

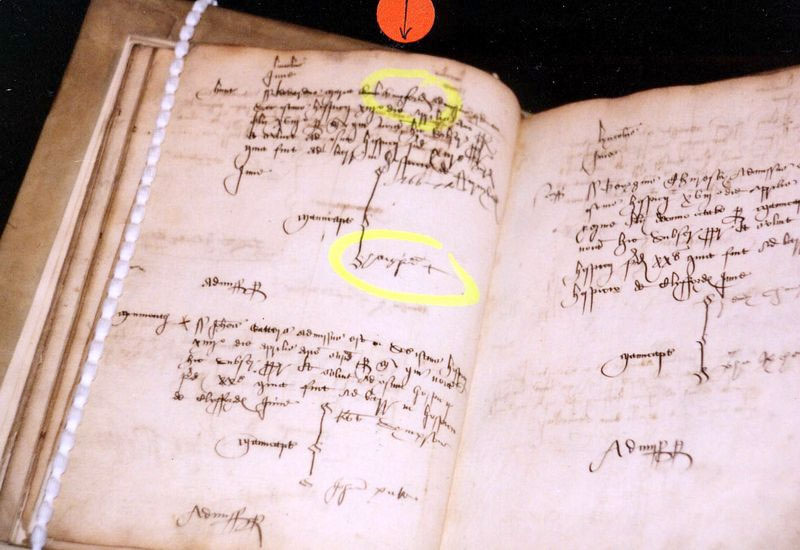

35 See my article below about The Stonely Deed MS22A/4 (courtesy of the County Record Office, Huntingdon). And see Plate 5.

Article: Copyright The Wingfield Family Society & Jocelyn R.Wingfield, 1999, 2001

The Stonely Deed, MS22A/4 Courtesy of and Copyright The County Record Office, Huntingdon, 2001

In 1993 the Wingfield Family Society (W.F.S.) published in the USA my Virginia’s True Founder: Edward-Maria Wingfield and His Times, 1550-c.1614, the first biography of Edward-Maria. I took his approximate date of death from the Visitation of Huntingdonshire, 1613 and The Visitations of Norfolk, 1563, 1589 and 1613, which had him living in that year (and no one had ever found a trace of him after that). However, signposted by Philip Burkett of the Kimbolton Historical Society, in 1996 I located Manuscript M22A/4 in the Huntingdonshire Record Office, Huntingdon, which shows that Edward-Maria Wingfield was alive on October 23, 1619. The same document also bears his only known signature – the only signature of note missing from Alexander Brown’s Genesis of the United States (1964). This manuscript is in a poor state, but my transcription of it from the seventeenth century script (adding minimal punctuation where vital), together with my historical footnotes, courtesy of the County Rceord Office, Huntingdon, here appears in print for the first time. It is an important historical document, since it all but proves that the four branches of the Wingfields – the lines of Letheringham (Suffolk), of Ireland/Hampshire, of Kimbolton and of Upton (both in Northants) – all knew the key players in the Virginia venture, such as the Pophams and Mildmays (and later Throckmortons), as I showed in “Virginia’s True Founder”.